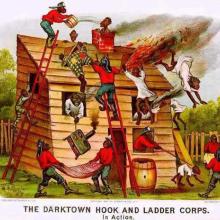

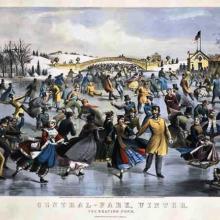

The firm Currier & Ives, self-described as “publishers of cheap and popular prints,” is well known for depicting scenes of American life, showing people at work in the building of cities and railroads; Currier & Ives also produced lithograph prints of American families at play, with their images of holiday winter scenes and sporting, patriotic, and historical events. The impact of their images on the American imagination was far-reaching: In their 73 years (1834-1907) of producing at least 7,500 lithograph images, two to three new images every day, the firm defined life for the industrious American middle class. Thanks to the Allen and Mary Kollar fellowship for students doing work on literature and the visual arts, graduate student Melanie Hernandez was able to travel to the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, to study a little-known archive of grotesque Currier & Ives images that is uncharacteristic of the rest of their catalogue, a collection called the Darktown Series.

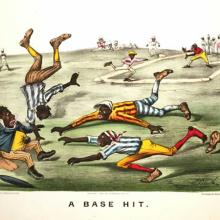

Unlike images in their general catalog, Currier & Ives’ Darktown Series depicts recently freed, upwardly mobile African Americans “play-acting” at being white, but every endeavor runs amok, ends in disaster, and frequently ends in bloodshed. These cartoon images were apparently meant to be funny. Hernandez undertook a complex cultural reading, revealing the particular ideologies of race at play in these constructions: “The violence in these images is enacted on black bodies, but is not enacted directly by white people. Instead it is inferior biology or fate intervening, an invisible hand or self-inflicted injury that causes the bloodshed and violence.” The implication is that the character in the lithograph is someone who aspires to a position that is beyond his/ her capability, so Nature or Fate will intervene to maintain the so-called natural order. These images supported the late 19th-century paternalistic and pseudoscientific arguments that enslaved Blacks benefited by being close to and protected by their white masters.

These Currier & Ives images are distinctly different from the lynching photographs common during this historical period because the Darktown Series conceals who is performing the violence. Currier & Ives was not the only Northern publisher producing similar images. Earlier comics circulated in antebellum illustrated periodicals take as their thematic content concerns over the rise of the black middle class, but the tenor of those comics is more lighthearted than the violence narrated in Darktown.

Hernandez notes that her archival work took her in an unexpected direction-children’s literature. Like the progression from lighthearted fun to gruesome violence documented in adult visuals, Hernandez tracks a similar trajectory in children’s literature at this same time period. Amongst others, she compares several versions of a popular children’s picture book, Ten Little Niggers, noting that the illustrations also grow increasingly violent as the 19th century progresses towards post-Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. According the Hernandez, “These books taught whole new generations about racist hatred.”

After the turn of the 20th century, Currier & Ives went out of business; as a consequence, all of their lithograph stones were destroyed except the Darktown Series, which was sold at auction and believed to have ended up in England. Hernandez discovered that a lot of collectors don’t want to display or sell the Darktown Series because it is now seen as a shameful part of a collection; however, there remains a very small audience within museums and archives that has remained interested in the series. Hernandez argues that “the way these prints have operated socially is comparable to the way other artifacts like lynching photos have. However, the Currier & Ives comics erase the violence that they do because they were considered funny, so the viewer didn’t have to take them as seriously.” Hernandez is asking on the one hand, “What is the work of comedy? What is the violence that comedy can do?” and on the other hand, “Did these images operate as revenge fantasy for white audiences, a place in which violence to African Americans is excused and allowed?” Hernandez wants “to help readers understand the kind of injury that cultural images can do. It is important to study cultural artifacts, not to treat them as disposable ephemera.”