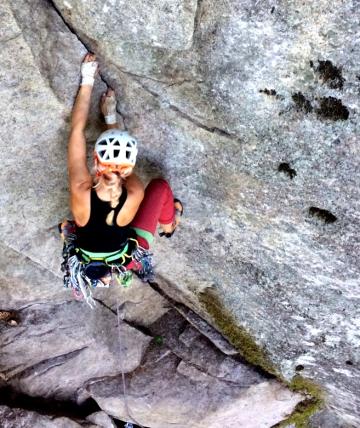

Alysse Hotz, like all of our graduate students working on Ph.D.s, pours blood, sweat, and we hope an absolutely minimal number of tears into her dissertation. What’s not so typical is Hotz’s living arrangement for much of this work. For as much of the year as can be made to work around her on-campus commitments, Hotz writes her dissertation on the road in her van. Why does she choose to, literally, park her laptop in dusty lots and campgrounds? Look to the horizon; our campus is surrounded by mountains, and those mountains are largely made of granite, and some of that granite is oriented straight up and down. Early in her career with us at UW’s English Department, Hotz was bitten hard by the climbing bug. Now she negotiates life between scholarship and rock and gravity, taking lessons from each area into the other along the way. English Matters caught up with Hotz to discuss how her passion for climbing intersects with her passion for social justice.

What first got you up in the mountains rock climbing?

Sounds like you’re immersed in some interesting sub-cultures. What’s your experience as a woman in the maybe stereotypically male domain of wilderness sport?

Misogyny, as is the case with the rest of US culture, is ever present within the climbing community -- be it males presuming you don't know what you're doing with your equipment and systems, assuming that a woman in a male/female party must be the girlfriend of the male (and not a partner/leader), or feeling the need to "spray you down" with unsolicited beta (“beta” refers to information and instructions on how to perform particular moves on a climb) when you're climbing. Indeed, since climbing was such a male dominated sport for so long (which is arguably no longer the case – I climb with as many female “crushers” as men), there are many challenges that women face climbing, especially within the bro-y-er sects of the climbing community. I am lucky to have a strong community of climbing friends who work actively to call attention to the harmful effects of these sorts of behaviors and practices, and I’ve also had the opportunity to work on two all-female first ascent teams over the past year, which has been incredibly inspiring.

So yes, there are challenges faced by women climbers in a historically male dominated sport, but I don’t think it’s wise to exceptionalize the forms of misogyny that permeate climbing culture, as it’s not much different than most communities I'm a part of-- academia, organizing, other social and collective groups - it just looks a little different in the climbing setting. As my dissertation argues in general, exceptionalizing some forms of violence disavows the forms of violence that also structure other ostensibly more progressive cultures/communities, as if these social formations weren’t cut from the same cloth of U.S. liberalism.

To what extent do you find fear to be a factor in your climbing experience? What do you learn from fear?

At the beginning of this most recent season, I climbed a 700 foot wall (a 6 pitch route called Outer Space in Leavenworth), and almost had a complete meltdown on a traverse pitch where there had been recent rockfall. All the holds felt loose and the climbing was more difficult than expected. Multiple times throughout the climb, but especially on that pitch, I felt like I was going to panic, but in the moment you cannot afford to shut down, so instead you go into a kind of hyper-focused mental state. “Pushing grades” that are difficult for you can be scary, but it's incredibly exhilarating and satisfying to push past that fear and be confident that you have the skills and knowledge needed to complete a lead climb safely and effectively. Confronting fears/anxieties through climbing has been incredibly helpful in managing fear/anxiety/stress in my academic and personal life as well.

It sounds then like climbing leaks off the mountainside and improves your work and personal life too?

I spend so much of my time as an academic working independently – reading and writing in isolation, being in my own head – so it's fantastic to push myself mentally and physically in these other ways through my climbing. I absolutely love the feeling of getting on a climb that kicked my butt a year ago and finally being able to pull the moves, put the rope up, send it clean. And I've met so many amazing people! There is something really special about spending such intense amounts of time with a group of people who were very recently strangers. Climbers follow a common migratory circuit, so I’m regularly treated to the delightful circumstance of showing up to a destination and running into old friends. And you constantly meet new friends who will become part of your "climbing family" in the future. It's a fascinating community that is not fixed and possessive but constantly moving and sharing and expanding. Climbing is demanding/challenging/scary, but there's no better feeling than spending a day on a granite wall with your friends, coming back to camp at the end of the day to share stories about struggles and successes over beers, food, and a fire. When it's good, there's literally nothing as much fun or as satisfying that I can think of doing with my time.