I met Roger Sale in the summer of 1972, very shortly after I had arrived in Seattle from UC Berkeley as a new assistant professor. I first heard about him from Alan Fisher, another faculty member who was to become one of my closest friends. Alan had painted Roger as larger than life—though not in the most standard of ways. “Roger,” Alan told me, “will bet on anything. If two birds are sitting on a fence, he’ll take a bet on which one will fly away first.”

A few days later I met Roger himself—he was in the department lounge playing cards with a group of graduate students. It was a noisy game, with fists banging on the table and bids barked out for every hand. A version (as I later learned) of bid whist, it was called Piss and Moan by its players—a name allegedly suggested by someone who put a head into the room in the game’s early days and asked, “What’s all this pissing and moaning about?” Though Roger had not instigated this game, he had become a full-throated participant, and remained at the P&M table for the next thirty years.

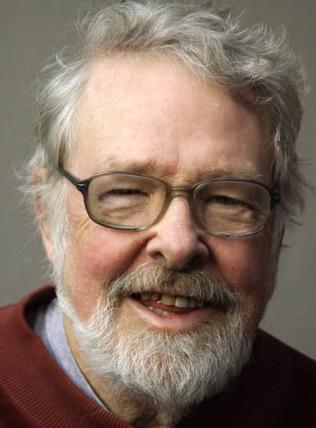

I describe just one of Roger’s communities here. Ours was important for him and for us, but Roger was a deeply and widely social man and had many other strong friendships as well. Some of this derived from his varied teaching interests—no one could match the range of things he taught: the Bible as literature, the 18th century novel, Children’s Literature, Composition, Modernism, Chaucer and Shakespeare, and late in his career, Women’s Literature as well. But the fact is that Roger loved people and he loved good talk, and he made many of us the better for it.

As a colleague, then, Roger was a dominating figure and, oddly enough, both fully successful as an academic and at the same time one who resisted almost everything about being one. Yes, he wrote thirteen books, but each one in its way pushed back at established views, opened new space, offered ways of talking about books both famous and not. Nowhere was this contrarian impulse clearer than with Modern Heroism (1973)—whose three “heroes,” quite unconventionally, were D. H. Lawrence, William Empson (the man Roger would say had taught him to read!), and J.R.R. Tolkien. Great writers, to be sure. Heroes? Roger told you how.

Fairy Tales and After (1979) was another hugely influential and contrarian exercise about material that “serious” critics had rarely noticed, let alone embraced. Roger wrote with dexterity and imagination about Peter Rabbit, The Wind in the Willows, and, for me most memorably, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I was enchanted by his close readings of the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party—and by the perceptiveness of his explanation of what it would mean to butter a pocket watch.

Nor was I the only one: this book struck a chord with readers nationwide and led to a long list of lectures and seminars at other campuses across the country.

Interestingly, his portrait of J.R.R. Tolkein in Modern Heroism had led to his being offered the job of editor for the first edition of Tolkein’s Silmarillion—an offer he declined, he explained, because it was not a book interesting enough to promote. Typical of Roger, the fact that such a book would almost assuredly sell many thousands of copies (which of course it subsequently did), each of which would have paid him a royalty, did not change his mind.

Roger went on to write two more substantial academic books, Literary Inheritance (1985) and Closer to Home: English Writers and Places, 1780-1830 (1986), as well as to publish On Not Being Good Enough (1979), a collection of essays written over the better part of a decade for the New York Review of Books. And of course, his most popular books, and by far the best selling, were Seattle Past and Present (1978) and Seeing Seattle (1994)—books that connected him to the wider Seattle community, joining yet another social and civil circle.

So teaching mattered greatly to him, but his biggest contribution to UW students might have been something he did less as a teacher than as a program director—and this was the brilliant remaking of the English Department’s Study Abroad in London program.

Although Roger and I probably share the UW record for numbers of programs taught and students shepherded through the streets, theatres, and pubs of London, it's also true that much of that would not have happened had it not been for Roger. For somewhere around 1985 David Fenner in the UW Foreign Study office approached us about institutionalizing what had been until that point only an occasional program. Instead of taking students to London just once every three or four years, David now offered us the chance to run a program every year. We accepted, and so was born what we named “The Literary London” program. As such it has run every year since, with an enrollment of first 30 students a year and then 60 when a few years ago we added a summer version as well. That adds up to 32 years of UW students making a life-changing trek to and through the streets of London with professors from the English Department.

That said, the program didn’t become transformative automatically. First someone had to solve the problem of how to design and administer an effective program held 5200 miles from Seattle. That someone was Roger, and his first move was to make an agreement with long-time friend and Londoner Peter Buckroyd to become our London administrator. That was smart, but his second move was smarter—to work with Peter to redefine the whole idea of a foreign study program. For Roger saw that the great challenge of teaching abroad was the difficulty of integrating one’s teaching into the lived lives and locations of the city you were in. Most programs were set in classrooms with occasional excursions, but Roger didn’t want a program like that. Instead he invented an Art and Architecture course that quite remarkably spent no time at all in a classroom but instead was taught entirely on the streets and in the great houses and museums of London. Twice a week, for two hours a meeting, he met his students in the West End—or in Pimlico, or under the Arches at Charing Cross—and took them through a wonder-tour of both famous sites and places no self-respecting tourist would ever go. Combine this with other courses similarly integrated into London life and Roger believed you had a chance to achieve the Holy Grail of teaching: fully authentic learning that engaged students not just intellectually but physically and emotionally as well. Since the invention of that model, well over a thousand students have gone through the program, a great number of whom would emphatically declare it to have been among the most important parts of their university lives.

I could go on. Roger was so much to me: colleague, critic, moral presence, car-pool member, stick-in-the-mud, Christian, intellectual hero. As it is for many of our English Department graduates, it is easy for me to say that Roger made my life—as well as the life of our entire department—more interesting, more complex, and enormously more fun.