[hover over pictures for captions and credits -- Ed.]

By Jessica Burstein, May 2018

Peter Buckroyd walks fast. You understand this from the very first day of the London Study Abroad Program. You’re probably still a little jetlagged, and the fact that cars are coming from the other direction is very much on your mind, but meanwhile your brain will have relayed this fact to your feet—or perhaps it’s the other way round. “Peter Buckroyd walks fast.” No matter the neural pathway—one of many new ones that will be laid in the weeks to come—you will know this.

By the end of the first day, whether it’s the spring or the summer program, you may be wondering what you signed up for. Or rather you will know what you signed up for, but you will be wondering if you can keep up with what you signed up for. But you will keep up. And the weeks of learning to look will have changed not only your eye but your mind. You probably will be walking a little faster too, craning your neck to look up at an architectural detail (silly caryatids in the Euston road; are those church arches pointed?) or down at where the servants’ entrance once was a few hundred years ago. In examining a 1700s garden you may well wonder whether the slave trade financed it, and how the heated debate between the early twentieth-century suffragists and the suffragettes on how best to achieve getting women the right to vote (“Deeds not words”) influences what you think of today’s politics.

Study abroad is after all not just about looking and listening; it’s about finding your voice. The impact on students is immeasurable. With Buckroyd’s “curiosity and zeal about all aspects of London’s art and architecture,” Sierra Stella, a current spring-in-London student, sees herself as “converted …into an active observer rather than a passive onlooker.”

Buckroyd is as they say a Renaissance man, with a D. Phil. on 1700s British tragedy, and one who has continued an extraordinary publication record while making this Program go: publishing a book on satire, editing collections on the poetry of D. H. Lawrence (Why? Because Buckroyd thought he wouldn’t like the poetry and he wanted to understand it; he now understands it), several different editions of Oscar Wilde plays; articles ranging from how to teach To Kill a Mockingbird to what is now his regular theatre reviewing for the Stratford Herald. His articles pull no punches, and he does not privilege fame. “Just at the moment when the Royal Shakespeare Company is butchering Shakespeare with its dreadful production of Macbeth, Tread the Boards Company has come to his rescue. He is still alive and well and living in Stratford but he has moved his residence to The Attic [Theater]."

Buckroyd also has a shadow life that is in fact blazing in England if your child is of school age and looking to get into university: he has been Chief Examiner in English literature for the GCSE, the national General Certificate of Secondary Education.

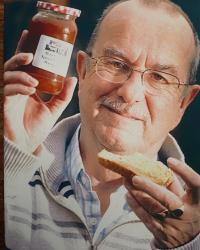

And in his copious free time Peter Buckroyd makes marmalade. He does so because, as with teaching, it brings him pleasure. And as with teaching, he does it brilliantly—since first entering his marmalades into the World Marmalade Competition in 2012, he has won bronze and silver medals every year he has entered (sometimes both in the same year). This year the coffee marmalade took the 2018 bronze. (Fortnum & Mason wanted him to sign a contract. He did not. Why? He does it for the pleasure, on his own terms, with an eye toward outcome, not output.) Reader, he has been queried. Reader, he will not say what his favorite flavor is. Nonetheless, two of his recipes will be available in a forthcoming World Marmalade Competition Cookbook. And for those unaware, competing over marmalade is, in England, a blood sport.

Sale and Webster went on not just to teach in the program but to direct it as it flourished. At Sale's retirement, the directorial mantle was passed to Shakespearian scholar William Streitberger for 13 years, then to Webster for seven years, and, as of 2017, (full disclosure) to this cub reporter, who admired its impact on students to the degree that she was able to (overfull disclosure) overcome her fear of Excel sheets.

With his scholarly and practical theatrical background Buckroyd first taught what would become another staple of the London program, its contemporary theatre course. All students (even those not in the theatre class) are able to attend a play a week—from big West End productions to “fringe” plays—the equivalent of off-off-off-off Broadway. The class goes to Stratford to see the Royal Shakespeare Company on site (it won’t be seeing Macbeth this year, opting instead for an excellent Romeo and Juliet), perhaps paying their respects to the actors who turn up at the pub Buckroyd knows they’re likely to be hanging out in after the play. The class returns to London to become “groundlings”—as in “you stand for the show in the pit of the audience directly in front of the stage,” as was historically the case—in the audience of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London.

But if the play’s the thing, it’s not just the directors who make a program work. There is a cast and a crew: Amy Feldman-Bawarshi has recently taken over as the London Program advisor and brought it to new heights. Feldman-Bawarshi was preceded by the indefatigable Bridget Norquist, with Sherry Laing before her—and Nancy Sisko providing the throughline, quietly monitoring the proceedings as the Director of Advising. For students, this is often where the program begins: as a mention by an advisor. “Given your schedule, why not….?” A life is thus changed. The Department’s Carolyn Busch quietly but steadily makes sure things happen at the nether reaches of administration, knitting that back into the practical fact of whether those theatre tickets were indeed purchased. And then there was the extraordinary Janet Dunlop, on the other side of the pond—gracefully overseeing the program’s homestays for 30 years, and coordinating the students’ orientations alongside Peter, explaining how American students tend to “graze” throughout the day while the British don’t snack.

Since the London Program uses homestays, placing students with London families throughout the city, students live as Londoners, which inevitably requires some recalibration (“no clothes dryer?”). Students commute in to wherever a class is being held—and like (or now, as) a Londoner, they learn to expect that as a real part of one’s life in the city, with frantic texting when the inevitable unforeseen occurs: “The Bakerloo Line is totally delayed.” “I hate the Bakerloo Line.” “Oh? I love the Bakerloo; did you see the Sherlock Holmes wall art?” “I saw Lestrade at the Shepherds Bush Theatre last night in the audience.” “Yeah: Rupert Graves.” “Who is Lestrade?” (Collective sigh heaved by Sherlock fans.)

So Peter Buckroyd walks fast. But in 30 plus years he has never lost a student. And the students have, in a new sense, found themselves.