Will Generative AI end college writing as we know it?

This question may strike you as a bit alarmist. But after surveying the proliferation of thinkpieces announcing as much—on top of the ambient sense that AI’s reign has only just begun—one would be forgiven for asking.

Take one of the first broadsides in what we might call an emerging genre: The Atlantic’s “The College Essay is Dead.” Published just one week after ChatGPT debuted in November 2022, writer Stephen Marche asserted that “nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia.” Two years later, the debate rages on. Recent essays in The New Yorker and The Chronicle of Higher Education are asking, “Will the Humanities Survive Artificial Intelligence?”

Fortunately, three members of the UW English Department are tackling that question head-on.

Over the 2024-25 academic year, Associate Teaching Professor Megan Callow, Assistant Teaching Professor Calvin Pollak, and Acting Assistant Professor Ben Wirth have been investigating the impacts of Generative AI technologies on the teaching of writing. As part of their Simpson Center research cluster, “A Classroom-Centered Inquiry into Generative AI, Large Language Models, and Writing Praxis,” Callow, Pollak, and Wirth have brought much-needed AI conversations to the department and the University of Washington at large.

While the cacophony of AI hype in the media may have amplified the cluster’s urgency, Callow, Pollak, and Wirth aimed to slow down and reflect on the more foundational features of sound writing pedagogy in this new AI-mediated landscape. Says Wirth, the cluster was meant to "have us all start thinking reflectively on what these technologies mean for writing pedagogy: why do we assign writing, what do we hope to achieve with these assignments, what are we trying to assess and evaluate, and how are these basic goals impacted by the availability of semi-accurate text generation.”

But first, they had to get everyone on the same page.

Defining the Debate

The cluster—which grew to be comprised of colleagues from Business, Philosophy, Landscape Architecture, and the Center for Teaching and Learning—spent the Fall quarter identifying relevant readings and drafting a teacher training structure. There, they observed that many of the stakeholders involved in conversations about GenAI in higher education were operating with different assumptions or talking past each other.

So, Pollak says, they went a little old school: all the way back to Hermagoras’ theory of stasis. “Many people were talking past each other because they were concerned with different stases of genAI (fact, definition, value, or action),” Pollak said. “Or, they lacked a basic common understanding of the technical facts and were jumping straight to moral posturing or one-size-fits-all policy prescriptions.”

With this realization, their objective came into view: giving faculty a “firmer grounding in facts and definitions relevant to AI text generators” so that instructors can make their own decisions about the value of AI tools, as well as whether or not to use them in class. Cutting through all the hype allowed the cluster to see more clearly—and critically—how these technologies operate.

Wirth echoed the emphasis on faculty empowerment:

I think a lot of instructors across disciplines initially approached these topics with fear and/or anxiety, so the opportunity to bring folks together to think critically about these issues has been a great opportunity. Our goal has been to let instructors learn and experience, and to encourage everyone to join--from the skeptics, to the curious, to the believers.

Through its focus on supporting instructors with regular meetings and public lectures, the research cluster ably demonstrated, in the words of Callow, that “there is a community of support available to them.”

Critical Engagement with AI and Being the “Human in the Loop”

In Winter, the cluster brought in Heidi McKee, Professor of English at Miami University, for a public lecture and workshop titled, “GenAI & Writing Across the Curriculum.” McKee has been at the forefront of both writing about GenAI in Writing Studies and experimenting with it in her writing classrooms.

In her lecture, McKee identified how she integrates GenAI tools in her writing instruction. While keeping the limitations of GenAI’s model in mind—including issues like bias, environmental impacts, and privacy considerations—McKee identified how fostering digital literacy, participating in societal decisions, and providing professional preparation are key upsides to integrating the technology critically into classrooms.

Rather than seeing Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT as a replacement for the writing process, McKee stressed that instructors can integrate LLMs into different stages of the writing process—whether invention, drafting, revision, or editing—thus requiring students to engage with it intentionally and iteratively. Above all, McKee emphasized that AI usage should prompt an open dialogue between students and instructors about how this tool can aid in, not replace, critical thinking—and that we should impress upon our students the necessity of being the “human in the loop.”

McKee’s students even came up with an apt metaphor: AI as a bicycle. They wrote,

Just as a bicycle can take me farther than if I walked but it still is my exercise that is shaping the experience, so now do I see how AI can improve my writing without replacing the mental exercise of the writing process. Writing with AI still requires exercising knowledge and skills, just as a bicycle does, and provides endless room for improving on those skills and developing that knowledge.

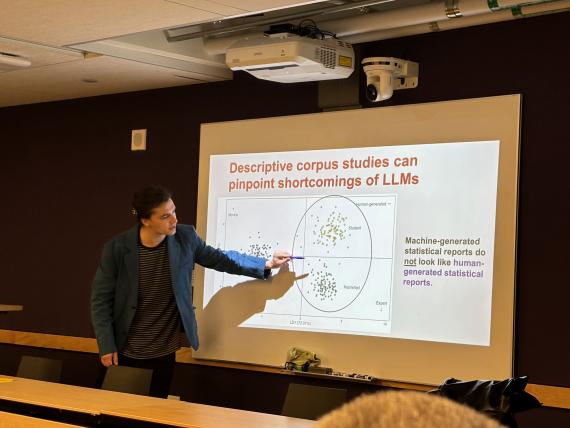

This Spring, the cluster brought scholar Mike Laudenbach,of the New Jersey Institute of Technology for a talk titled “The Rhetoric of Generative AI: Leveraging Corpus Methods for LLM Text Analysis.” Laudenbach brought a different perspective on LLMs to the research cluster’s audience, using data modeling and corpus linguistics to identify stylistic differences between LLM- and human-generated writing.

Reflecting on the event, Pollak says he was intrigued by Laudenbach’s finding that LLMs “love the word ‘tapestry’ and the future-tense verb ‘will,’ but almost never use modal verbs like ‘could’ or ‘would.’” (This reviewer now knows which words he’ll be leaving out of his next article.)

Pollak contends that Laudenbach’s research can do more than help us identify when students are relying too much on LLMs: it can also “help us focus our teaching on specific writing styles and techniques that students can use in order to sound more ‘human’ than their peers and colleagues who are thoughtlessly using AI.”

Sound Writing Pedagogy in the AI Era

The feeling one gets in hearing from these three faculty members is that the emergence of GenAI technology makes the expertise of writing instructors more vital, not less. The capabilities of Large Language Models enable instructors to re-focus on the writing process itself over the finished product. This, in turn, means a return to the sorts of evidence-based teaching practices that students benefit from: scaffolded writing projects, regular feedback and dialogue, and an iterative writing process.

As Callow reflects, GenAI may “offer some really helpful support in the writing process. For example, my students found it pretty useful for generating search terms as we were kicking off a research project,” though she also cautions that different disciplines or fields will necessarily have different relationships to the technology.

Pollak concurs, adding: “AI tools are very much human systems and products…AI is an opportunity for [writing instructors] to double down on the critical and rhetorical skills that we teach our students, because these skills will help them to both write effectively if they wish to use AI as part of their processes and read critically the text generated by AI.”

It seems that, for now, Generative AI is here to stay. But so, too, is sound writing pedagogy, developed by instructors making informed decisions about how—or how not—to engage GenAI as a tool for deepening learning, rather than as a substitute.

Hopefully, that is one thing we can all agree on.

The research cluster’s program concluded on May 21 with a Hackathon for “Teaching with Large Language Models.”